The mainstream theological tradition has been amillennial since Augustine, and therefore the question of the “millennium” (Rev. 20) has not been a matter of major concern for most major theologians. Evangelical theology, however, has typically been very focused on this question. So Donald Bloesch writes,

“Apart from biblical inerrancy no doctrine has caused greater division in evangelical Christianity in the present day than the millennium. Though the biblical references to a millennial kingdom are minimal, they have given rise to elaborate theologies based on the reality of such a kingdom. Because the millennial hope has been a source of inspiration to Christians throughout the history of the church, impelling many toward a missionary vocation, it merits serious consideration.” Donald Bloesch, Essentials of Evangelical Theology (New York: Harper & Row, 1978), II: 189.

There are three basic positions on the millennium, along with one important variant on the premillennial position.

There are three basic positions on the millennium, along with one important variant on the premillennial position.

Amilliennialism: Revelation 20 is symbolic, not literal, so there will be no 1000 year reign of Christ on earth. The millennium refers to Christ’s present rule during the church age. Christ has already bound Satan in the resurrection, though it is a relative binding. Christ will return and the final judgment will follow.

Premillennialism: Christ returns before a literal 1000 year reign on earth in which he reigns directly over the world. Tends to be pessimistic about the possibility of any cosmic or social redemption before Christ’s return – in fact, things will get worse and worse before the parousia.

Premillennial dispesationalism: divides salvation history into different “dispensations” in which God relates to people in different ways. There are two parousias: the first at “the rapture” when Christ returns to remove the church from the world; then he returns again at the start of the millennium seven years later.

Postmillennialism: Christ will return after a millennial period in which his reign is exercised triumphantly on earth through the church. The gospel will be taken to all nations, and will hold sway over the world. Evil will still be present, but will be subdued by Christian influence during this golden age of the church.

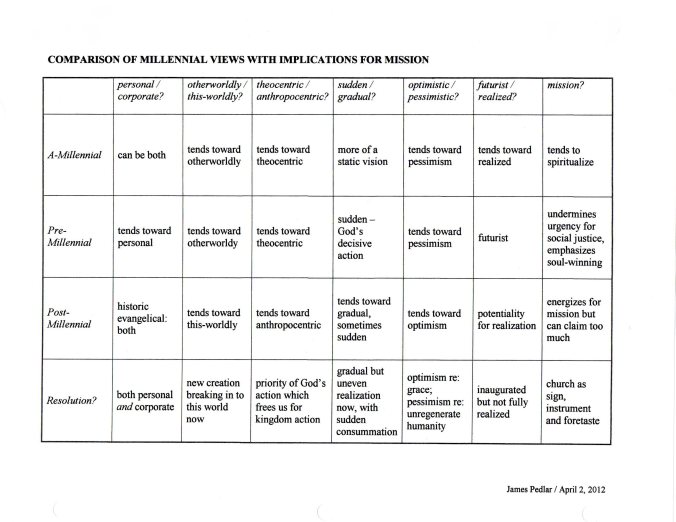

I was lecturing on this topic a couple weeks ago, and in an attempt to help students get a handle on these debates I proposed six different sets of tensions that are at work in eschatological debates. These could be seen as differing emphases within the various eschatological visions that have exercised influence in the church over the centuries. Each of these is a set of “poles” which could be seen as existing on a continuum, and any given theologian might tend more towards one pole or the other.

First, there is a tension between personal and corporate eschatologies. Any full-orbed eschatology will deal with both personal and corporate dimensions, but some tend to push more in one direction or the other. That is, some eschatologies focus more on the fate of the individual: the eternal destiny of the saved and unsaved; questions of how we will be judged; what the resurrection body will be like, and so on. On the other hand, some eschatologies are focused more on the corporate dimensions of God’s plan for the eschaton: the future kingdom of God; visions of social justice, the overcoming of inequalities; the reconciliation of different people-groups, and so on.

Secondly, there is a tension between otherworldly and this-worldly eschatologies. Those eschatologies which are more otherworldly will focus on the radical difference between the future kingdom and the present life. They will stress discontinuities between the world as we know it and the future which God has planned for us. On the other hand, this-worldly eschatologies will tend toward a more “realized” eschatology, and see the kingdom being formed here and now in various ways. They might be uncomfortable with heavenly visions and prophecies, and seek ways for eschatology to have impact in the world here and now.

Thirdly, there is a tension between theocentric and anthropocentric eschatologies. Eschatologies with more theocentric tendencies will emphasize God’s decisive intervention in world history, both in present anticipations of the kingdom and in its final consummation. Human beings are likely portrayed as having little real agency in ushering in God’s kingdom. Theocentric-tending eschatologies might also tend towards more deterministic views of history, stressing God’s control over world events. Those with more anthropocentric tendencies will stress the role of human agents in bringing the future kingdom to realization. Human beings, with God’s help, will be seen as capable of moving history toward its proper goal and the purpose for which God created it.

Thirdly, there is a tension between theocentric and anthropocentric eschatologies. Eschatologies with more theocentric tendencies will emphasize God’s decisive intervention in world history, both in present anticipations of the kingdom and in its final consummation. Human beings are likely portrayed as having little real agency in ushering in God’s kingdom. Theocentric-tending eschatologies might also tend towards more deterministic views of history, stressing God’s control over world events. Those with more anthropocentric tendencies will stress the role of human agents in bringing the future kingdom to realization. Human beings, with God’s help, will be seen as capable of moving history toward its proper goal and the purpose for which God created it.

Fourthly, a related consideration would be the tension between sudden and gradual eschatologies. Some theologians emphasize a sudden and dramatic change that will take place at the end. In this view, we may not see any real “progress” towards the kingdom prior to that sudden, cataclysmic event. In fact, things might get worse before God suddenly intervenes to bring about the final consummation. On the other hand, others might emphasize gradual change and growth, leading to the kingdom. In extreme cases, some have supposed that there would be no dramatic change at the end at all, but a gradual development and progress until one day God’s kingdom is established on earth.

Fifthly we could talk about pessimistic and optimistic eschatologies. Here the optimism or pessimism relates to the degree to which the eschaton is breaking into the world today. Some have little hope for present realization of the eschatological kingdom, and instead look upon the world around us as a discouraging place which is wasting away. Others see signs of the kingdom and are optimistic that things really can improve here and now. Obviously those who have otherworldly, theocentric, and sudden eschatologies will likely tend towards pessimism, whereas those with this-worldly, anthropocentric, and gradual eschatologies will tend towards optimism.

Finally, there are futurist and realized eschatologies. Obviously, echatologies with more futuristic orientations will orient there hope to the coming consummation of the eschaton, and be less hopeful about the present age, whereas those whose eschatologies tend towards a more realized perspective might have less focus on the future hope, and more focus on hope for present transformation.

Using these sets of “tensions,” I’ve developed the following analysis of the millennial positions, with my suggestions regarding how potential strengths of each view could be integrated. This probably needs further explanation in a separate post, but I’ll leave it here for now – comments and suggestions would be welcome.

The fact that he was a Harvard professor meant nothing to these people. He was used to relying on his credentials and his accomplishments to impress everyone, but suddenly he was put into a place where people didn’t care about how many letters he had after his name. He continues,

The fact that he was a Harvard professor meant nothing to these people. He was used to relying on his credentials and his accomplishments to impress everyone, but suddenly he was put into a place where people didn’t care about how many letters he had after his name. He continues,