Hans Urs Von Balthasar’s The Office of Peter and the Structure of the Church presents the most intriguing accounts of charismatic movements in the Church I’ve encountered thus far. Balthasar provides an interesting example of an attempt to create legitimate space for radical movements of the Spirit within a robustly catholic ecclesiological framework. The particulars of his argument are strange, and difficult for a protestant to digest, but his approach is sophisticated, and deserves engagement. I include it under the “charismatic in legitimate tension with institutional” type, along with Rahner, but as a bit of an aside, given that the form of Balthasar’s argument is so idiosyncratic.

Hans Urs Von Balthasar’s The Office of Peter and the Structure of the Church presents the most intriguing accounts of charismatic movements in the Church I’ve encountered thus far. Balthasar provides an interesting example of an attempt to create legitimate space for radical movements of the Spirit within a robustly catholic ecclesiological framework. The particulars of his argument are strange, and difficult for a protestant to digest, but his approach is sophisticated, and deserves engagement. I include it under the “charismatic in legitimate tension with institutional” type, along with Rahner, but as a bit of an aside, given that the form of Balthasar’s argument is so idiosyncratic.

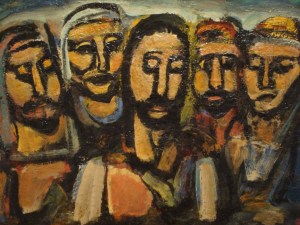

For Balthasar, the tension between stable orthodox Church structures and movements of renewal is inherent in the very nature of the Church. This is seen most clearly in his use of the concept of the “christological constellation.” Balthasar’s argument is that just as Christ cannot be understood apart from his relation to the Father and the Spirit, so also he cannot be understood apart from the human relationships which were central to his historical life on earth. John the Baptist, Mary, Peter, John, James, and Paul are all essentially related to Jesus and are therefore integral to christology (The Office of Peter, 136-137). As the historical foundation of the Church, the members of the constellation are interpreted by Balthasar as “Realsymbols” or structural principles on which the church is founded, and through whom the presence of Christ is mediated to the Church (Office of Peter, 226-227). Each member of the constellation is described according to their relationship with Jesus: the Baptist as a herald; Mary as the all-embracing perfect response to the grace of the Lord; Peter as one who participates in the authority of Christ in a singular way; John as the beloved who in love mediates between Peter and Mary; James as the one who takes Peter’s place in Jerusalem and represents continuity between the Old and New covenants; and finally Paul, the one untimely born who nevertheless takes the lion’s share of Christ’s mission, even though there seems to be no place for him among the college of the apostles.

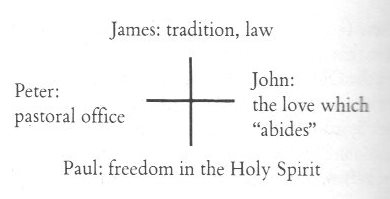

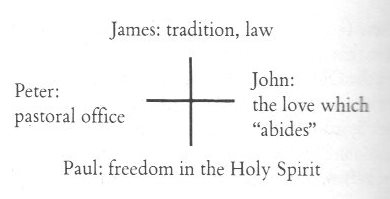

Because the Church did not emerge en bloc, but is founded on the prophets and apostles, the particular relationship of each of the members of the constellation is prototypical for the Church. Specifically, after Pentecost, Balthasar argues that there is a fourfold structure of the Church which emerges: the Pauline, Jacobite, Johannine, and Petrine aspects of the Church. He sketches the constellation like this:

These are the four ways in which the Church is embodied in the world, and every community and every individual Christian life takes shape amid the tension and dynamism that exists between these poles. The Church “expresses itself concretely in the dynamic interplay of her major missions and in the laws inherent in her structure” (Office of Peter, 314-315).

In Balthasar’s scheme, the orthodox structures of the Church are interpreted as the Petrine and Jacobite aspects, while the movements of renewal are interpreted as Pauline. Obviously the Petrine aspect of the Church is seen in office, and the Jacobite aspect is seen in Church law and tradition. What is specific about the Pauline aspect is precisely Paul’s uniqueness, his supernumerary relationship to the apostles, and the unpredictable way in which he was chosen for his task directly by the Lord. Because Paul is unique, his “successors” can only be identified by remote analogies as those who have charismatic vocations, whose recognition by those in office is compelled by divine evidence (Office, 159). The founders of religious orders are examples of such direct divine vocations, according to Balthasar. These movements of renewal are never founded by those in office, but by unexpected the founders of renewal movements, whose lives of sanctity “fall into the garden of the Church like a meteor” (The Laity and the Life of the Counsels, 67). Their divine vocations must be tested by those in authority, but once tested, their unique missions and “charisms” cannot be suppressed. These saints, “struck by God’s lightning,” ignite a blaze in those who gather around them, offering the Church hope of renewal and reform (The Laity, 42). The religious orders that have arisen unexpectedly in response to these movements are able to radiate their light into the whole Church, moving outwards in concentric circles from the point at which lightning has struck (The Laity, 88). The Petrine office is indispensable, but it is conceived by Balthasar as one aspect of the christological constellation, and must be seen in relation to the whole. Because the Spirit works in unpredictable ways as well as through the official structures of the Church, Peter’s task is limited to making judgments and rendering verdicts amid the tensions that arise in the life of the Church. He represents unity, but in so doing he must make space for others.

The unity of the Church is maintained when these major missions are understood in relation to the whole constellation. The challenge is to achieve a reintegration of the elements which are isolated, in order that the tensions inherent between them may be lived out fruitfully within the mystery of the Church as Body and Bride of Christ. In fact, the tensions between the principal figures of the constellation “all point to the mysterium; they are its necessary expression, not shortcomings on the part of the Church that need to be corrected by “changing its structure”” (Office of Peter, 24). The history of the church can even be described by Balthasar as “an evident contest,” between the various poles of the christological constellation (Office, 314). This process of contesting, for Balthasar, has a legitimate and community-creating value for the Church. The church as ecclesia semper reformanda takes shape as various poles in the constellation are put back in their place, and a proper balance between the various aspects of the Church is established (Office of Peter, 314). The tension between the members of the constellation is the “force field” which generates apostolic missions.

The unity of the Church is maintained when these major missions are understood in relation to the whole constellation. The challenge is to achieve a reintegration of the elements which are isolated, in order that the tensions inherent between them may be lived out fruitfully within the mystery of the Church as Body and Bride of Christ. In fact, the tensions between the principal figures of the constellation “all point to the mysterium; they are its necessary expression, not shortcomings on the part of the Church that need to be corrected by “changing its structure”” (Office of Peter, 24). The history of the church can even be described by Balthasar as “an evident contest,” between the various poles of the christological constellation (Office, 314). This process of contesting, for Balthasar, has a legitimate and community-creating value for the Church. The church as ecclesia semper reformanda takes shape as various poles in the constellation are put back in their place, and a proper balance between the various aspects of the Church is established (Office of Peter, 314). The tension between the members of the constellation is the “force field” which generates apostolic missions.

What I like about Balthasar’s approach is that he avoids a simple opposition between “institutional” and “charismatic” without giving too much ground in one direction or the other. His christological constellation is an innovative way of attempting to conceive of the complex human and divine reality which is the people of God. It provides a way for discussing the history of the Church as it relates to charismatic movements, without smoothing out the conflicts that have often ensued between the movements and the established Churches. The conflicts themselves are not so much a “problem” but an inherent part of what it means to be the Church. This means we don’t need to “resolve” the conflicts between movements of renewal and established structures by siding with one side or the other (as has often happened in Church history). The Church in her total reality needs both stable orthodox structures and unpredictable movements of renewal.

In the end, however, the particulars of Balthasar’s argument are a bit too idiosyncratic to be useful across ecumenical lines. The obvious problem (for protestants) with his approach is the high place which is afforded to the four apostolic figures in the ongoing life of the Church – even to the point of speaking of their “mediation” of Christ. To be sure, Balthasar absolutely upholds the uniqueness of Christ, and is not assigning salvific value or merit to the apostles. However, he argues (and I will grant that it is an interesting suggestion) that Jesus, fully divine but also fully human, cannot be understood apart from the human relationships he established during his life on earth, especially his relationships with those who were very close to him. Historically speaking, we can also see how these primary persons in Jesus’ inner circle became the nucleus of the primitive Church. Fair enough, but it is a stretch to move from these affirmations to four foundational principles for the Church in her continuing historical life. While Balthasar’s theory is loosely grounded in the biblical narrative, the connection to the actual scriptural witness is quite tenuous, and leaves us wondering if he’s reading Church history back into the character of the four apostles. Has he simply used these four biblical figures as a convenient means of conceptualizing what he believes are essential aspects of the Church? I suppose if you begin from a Roman Catholic perspective, and you already accept the special role assigned to Peter as an essential aspect of the Church for all time, then it is not too much of a stretch to discuss similar principles of ecclesial life as grounded in other apostolic figures. If that is the case, could his approach retain some merit, independently of the somewhat novel theory of these four apostles as Realsymbols of the Church? Can we gain anything from his approach, without buying into the mediating role that Balthasar assigns to Peter, James, John, and Paul? What would be left? A set of “principles” which are inherent to the life of the Church? On what foundation could such a set of principles be identified, if not on the basis of the apostles? On strictly historical grounds, we can see how the history of the Church, interpreted from a broadly catholic point of view, supports these affirmations. Should the lessons of Church history regarding renewal movements provide us with a normative basis for conceiving of the Church’s nature? I want to say yes, but I’m still sorting out the details of how the argument can be made.

People who have done research on The Salvation Army and the sacraments will probably be familiar with these quotes, but I find that a lot of people are surprised by some of the things that William Booth said about the Army’s non-observance of the sacraments. So I’m just putting these three quotes out there, as a follow up to my last post.

People who have done research on The Salvation Army and the sacraments will probably be familiar with these quotes, but I find that a lot of people are surprised by some of the things that William Booth said about the Army’s non-observance of the sacraments. So I’m just putting these three quotes out there, as a follow up to my last post.

In this way the charismatic element in the church is passed on through institutional means, which are courageously received and approved by the Church, as the charismatic movement in question submits to her authority and law. This aspect of “regulation” of the Spirit is, for Rahner, an essential part of the reform movement’s vocation, in which the charismatic element of the Church shows that it truly belongs to the Church and its ministry. Speaking of submission to the Church’s regulation, Rahner writes, “It is precisely here that it is clear that the charismatic element belongs to the Church and to her very ministry as such” (59).

In this way the charismatic element in the church is passed on through institutional means, which are courageously received and approved by the Church, as the charismatic movement in question submits to her authority and law. This aspect of “regulation” of the Spirit is, for Rahner, an essential part of the reform movement’s vocation, in which the charismatic element of the Church shows that it truly belongs to the Church and its ministry. Speaking of submission to the Church’s regulation, Rahner writes, “It is precisely here that it is clear that the charismatic element belongs to the Church and to her very ministry as such” (59).