Joan Chittister’s The Liturgical Year: The Spiraling Adventure of the Spiritual Life is part of the Ancient Christian Practices series, published by Thomas Nelson. Chittister, who has an excellent reputation as an author and speaker, is well qualified to write on this subject: as a Benedictine sister, she lives as part of a community whose life is profoundly shaped by the seasons of the traditional liturgical year.

The book is accessibly written, with 33 short chapters. The first eight chapters cover introductory topics, while the rest of the book is shaped around the liturgical year itself, beginning with Advent and continuing through Orindary time, with a few other topics interspersed as she goes.

Chittister sets the liturgical year in the context of the life of discipleship. Observing the Christian seasons is not simply a way to mark time, but it is a way to “attune the life of the Christian to the life of Jesus, the Christ” (6). By allowing the liturgical year to bring the life, teaching, death, and resurrection of Christ before us again and again, we learn what it means to follow Christ:

From the liturgy we learn both the faith and Scripture, both our ideals and our spiritual tradition. The cycle of Christian mysteries is a wise teacher, clear model, and recurring and constant reminder of the Christ-life in our midst. Simply by being itself over and over again, simply by putting before our eyes and filtering into our midst the living presence of Jesus who walked from Galilee to Jerusalem doing good, it teaches us to do the same (10).

This is possible because the liturgical year “immerses the Chrisitan in the life and death of Jesus from multiple perspectives” (27). Worship, then, is not simply about us expressing our feelings to God, or about celebrating what God has done. Worship is also formative; it shapes us in our faith and our life with Christ. I fully agree with Chittister on this point, that the liturgical year can and should be “a catechesis as well as a celebration, a spiritual adventure as well as a liturgical exercise.”

I do have some concerns with Chittister’s approach to the liturgical year, but before idenitfying some of them, I’ll say a bit more about the content of the book and its strengths.

Chittister notes that the liturgical year is not simply about the seasons of Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, and so on, but also includes Sunday observance, Ordinary Time, and (in the Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and some protestant traditions) the cycle of saints’ days. She offers some good insights about the message of the different seasons – far too many to note in this short review. But I since Advent is fast approaching I can give some examples from those chapters.

First of all, Chittister reminds us that, historically speaking, Advent was not the most important season of the liturgical year, and Christmas was not even celebrated until the 3rd century in Egypt, and even later in other regions (28). While Christians today seem to place the greatest emphasis on Advent and Christmas, it was Easter which historically formed the centre of Christian liturgical observations. She speaks of Advent as being about “three comings”: the birth of Jesus, the coming of Christ in our midst today, and the final return of Christ, and asks us to consider our own spiritual growth by asking ourselves which of the three we are waiting for (64-66). She also covers the traditional themes of the four weeks of advent, before spending a chapter reflecting on the basic character of Advent as a season of joy.

First of all, Chittister reminds us that, historically speaking, Advent was not the most important season of the liturgical year, and Christmas was not even celebrated until the 3rd century in Egypt, and even later in other regions (28). While Christians today seem to place the greatest emphasis on Advent and Christmas, it was Easter which historically formed the centre of Christian liturgical observations. She speaks of Advent as being about “three comings”: the birth of Jesus, the coming of Christ in our midst today, and the final return of Christ, and asks us to consider our own spiritual growth by asking ourselves which of the three we are waiting for (64-66). She also covers the traditional themes of the four weeks of advent, before spending a chapter reflecting on the basic character of Advent as a season of joy.

There is a lot of wisdom to be gained from this book, particularly for those of us who are evangelicals and are not steeped in liturgical tradition. I personally hope that many evangelical churches will embrace the liturgical calendar, at least to a greater extent than they do at present. While the observance of the various saints’ days is not likely to fly outside of Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican circles, following the major seasons in the church year can provide a way to root the focus of our preaching and teaching more consistently in the narrative of God’s saving action in history through Jesus Christ.

My concern with Chittister’s approach relates to the theological presuppositions that she brings to the table.

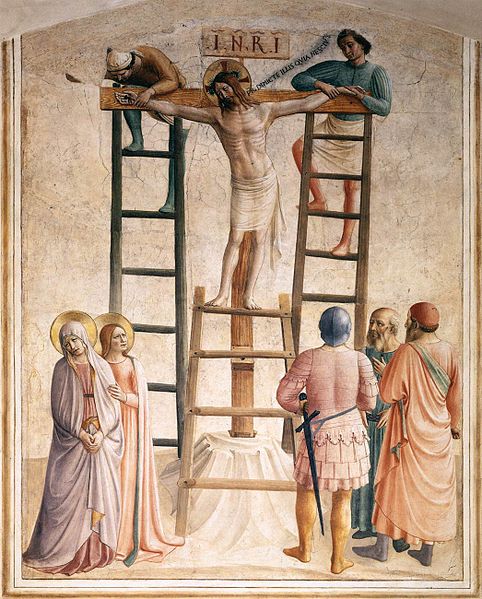

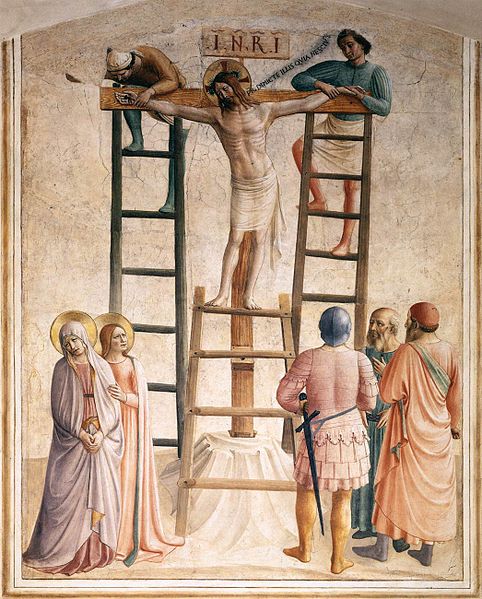

First, as a matter of emphasis, she seems to lean very heavily on Christ’s role as an exemplar for us, without a strong enough emphasis on the cross and resurrection as Christ’s work on our behalf. It’s not so much that she denies the latter, but I was sometimes bothered by what she was not saying.

For example, she says that “Jesus embodied what the role of the cross was to be in the life of us all” (15). While I certainly believe that all Christians are called to take up their cross and participate in the cruciform life of Christ, I wouldn’t say that Jesus’ death was simply the embodiment of what we are all called to be. Surely his death was more unique than that – the one, full and sufficient sacrifice for the sins of the world!

She continues in this vein,

It was, if anything, a sign to us of our own place in the scheme of things, in the order of the universe, in the economy of salvation. Now, it was clear, every capacity for good, every effort of anyone, every breath of every human being had significance…Now it became obvious: if the life of Christ was to continue here on earth, it must continue in us. Such an astonishingly piercing assessment of who Jesus really was and what that implies for those who call themselves Christian constituted a momentous breakthrough in the human awareness of the panoptic significance of the individual spiritual life (16).

It seems to me that Chittester is identifying Jesus as the greatest example of human spirituality – a person who inspires us to exercise our capacity for good. Perhaps I’m being unfair, but as I read the book I was thinking that, for Chittister, it is not the particularity and uniqueness of Jesus, but the realization of a more fundamental category of human potential that she thinks is the most important thing. In other words, it is not the saving work of Jesus Christ which is most fundamental, but the significance of the individual spiritual life, which is revealed in Jesus and enabled through our participation in him.

Another quote emphasizes this last point:

Finally, it is in coming to know the Jesus whose life was fine-tuned to the voice of God within him and whose death came out of unremitting commitment to the will of God, whatever the cost, that our own life is shaped and reshaped (41).

Here she frames the death of Christ as “unremitting commitment to the will of God” – a true statement, but one which is de-particularized in such a way that it becomes an example of that to which all human beings are called. Rather than the once for all sacrifice in our place, Christ’s death becomes the greatest example of doing God’s will.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that it is wrong to say that Christ’s death is, in one sense, an example of what it means to do the will of God no matter the cost. But I think that this emphasis can go astray if insufficient attention is given to the radical uniqueness of Jesus Christ and the sufficiency of his work on our behalf. We are called to follow after Christ, but that is about us being conformed to Christ’s likeness, not Christ illustrating a general standard of what it means to follow God. Rather than God incarnate, condescending to rescue humanity, Jesus becomes framed as the one who shows us “what it means to be a human on the way to God” (58). In her own words, this perspective turns the story of the death and Resurrection of Jesus into “the call to recognize the resplendency of humanity” (47). I see this as a skewing of the gospel narrative, turning it into the story of humanity’s ascent to God, rather than the story of God’s rescue of humanity.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that it is wrong to say that Christ’s death is, in one sense, an example of what it means to do the will of God no matter the cost. But I think that this emphasis can go astray if insufficient attention is given to the radical uniqueness of Jesus Christ and the sufficiency of his work on our behalf. We are called to follow after Christ, but that is about us being conformed to Christ’s likeness, not Christ illustrating a general standard of what it means to follow God. Rather than God incarnate, condescending to rescue humanity, Jesus becomes framed as the one who shows us “what it means to be a human on the way to God” (58). In her own words, this perspective turns the story of the death and Resurrection of Jesus into “the call to recognize the resplendency of humanity” (47). I see this as a skewing of the gospel narrative, turning it into the story of humanity’s ascent to God, rather than the story of God’s rescue of humanity.

Secondly, I felt that Chittister’s perspective was underwritten by a kind of mysticism. By this I mean that she seemed to presuppose that God is already always within us, and that our ultimate destiny is absorption into God and even into creation. She writes, near the beginning of the book:

The seasons and feasts, if we are open and alert to them, lead us deeper and deeper into the self, beyond the pull of the present, higher and higher into the One who beckons us on through time to that moment when we will dissolve into God, set free from time to become one with the universe (6-7).

I want to retain Luther’s insight that salvation is something that comes from without, not from within. We do not have the resources within ourselves to find salvation. We need the external Word to speak to us, and the Spirit to indwell us. But even this indwelling does not mean that we are called to go “deeper and deeper into the self.” Finally, becoming “one with the universe” does not seem to me to be a particularly Christian aspiration.

I hope I have not misinterpreted Chittister’s message, but I found these aspects of the book to be at odds with my own convictions.

This review is already getting too long, so I’ll stop there. If you want to learn about the liturgical year, this book provides a short, readable introduction, and contains some interesting perspectives. But I would urge the reader to be aware of some of the theological presuppositions that Chittister brings to the table.

Disclosure : I received this book free from the publisher through the BookSneeze®.com book review bloggers program. I was not required to write a positive review, and the opinions I have expressed are my own.