From 2007 to 2010, the Commission on Faith and Witness (Canadian Council of Churches) engaged its members in a dialogue regarding the role of doctrine in the life of the church. The fruits of this dialogue are reported in the current issue of Ecumenism, published by the Canadian Centre for Ecumenism in Montreal. Each commission member was asked to articulate their tradition’s answer to the following questions:

From 2007 to 2010, the Commission on Faith and Witness (Canadian Council of Churches) engaged its members in a dialogue regarding the role of doctrine in the life of the church. The fruits of this dialogue are reported in the current issue of Ecumenism, published by the Canadian Centre for Ecumenism in Montreal. Each commission member was asked to articulate their tradition’s answer to the following questions:

- What is dogma or doctrine in your tradition?

- What are considered to be doctrinal statements?

- Who can make doctrinal statements?

- What is the relation between doctrine and revelation?

- How does your tradition view the first seven ecumenical councils?

- How does your tradition understand the reliability of Scripture?

- What are those shared convictions without which the Church’s mission would be seriously impaired, or even become.

While ecumenical dialogues often aim at producing some sort of consensus statement, members reported that during this particular dialogue, it became clear at the outset that no consensus would be achieved. The membership of the commission is very broad, including Catholics, Orthodox, historic Protestants, radical reformation, and evangelical traditions. Some of these traditions are committed to holding fast to formal statements of belief (creeds and confessions), while others have historically been opposed to creeds of any kind.

In an introductory article, Gilles Mongeau, Paul Ladouceur, and Arnold Neufeldt-Fast note the general commonalities that they identified in the process:

Every member Church holds to the necessity of some doctrine, explicit or implicit, as a reference point. In all cases, one or more documents exist which lay out this doctrine, though the authority and form of these documents varies greatly. In all cases, Scripture, tradition, reason, and religious experience interact in some way in the emergence of doctrine. Similarly, the role of some form of reception by the community of the faithful is a strong component of all of the traditions represented. Finally, the presenters of the papers agree that the fullness of truth resides in God alone, and that the truth of doctrines is eschatological, that is, oriented to a future complete fulfillment or plenitude.

“Introduction to the Working Papers on Doctrine,” Ecumenism 179-180 (Fall/Winter 2010): 5-6.

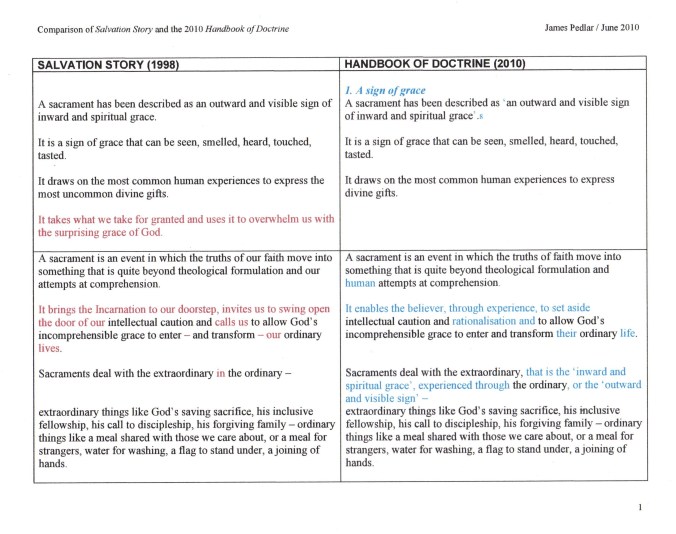

While I wasn’t part of the actual discussion, I was able to participate by revising and expanding the Salvation Army contribution to this publication, originally written by Kester Trim, and entitled “Doctrine in the Salvation Army Tradition.” It is interesting to consider doctrine in the SA’s life via a comparison with the role it plays in the life of other traditions. Some of our observations that are relevant to the above:

The Salvation Army is not known for placing a particular emphasis on doctrine. This is not because doctrine is unimportant for Salvationists, but because The Salvation Army has customarily emphasized evangelism and service, rather than theological scholarship. Nevertheless, The Salvation Army’s official doctrines are viewed as essential to its corporate life and witness.

“Doctrine in the Salvation Army Tradition,” Ecumenism 179-180 (Fall/Winter 2010): 36.

The Army is an interesting ecumenical partner in this dialogue, as it is on many issues, because it treats doctrine as essential, but tries to avoid doctrinal controversy. It wants its doctrine to be clear, but Salvationists haven’t wanted to spend much time developing their doctrinal tradition. It envisioned its brief 11 articles as a minimalist list of essentials, which would allow the SA to be “an evangelisitic force free from the entanglements of doctrinal controversy” (Ibid., 37).

The Army is an interesting ecumenical partner in this dialogue, as it is on many issues, because it treats doctrine as essential, but tries to avoid doctrinal controversy. It wants its doctrine to be clear, but Salvationists haven’t wanted to spend much time developing their doctrinal tradition. It envisioned its brief 11 articles as a minimalist list of essentials, which would allow the SA to be “an evangelisitic force free from the entanglements of doctrinal controversy” (Ibid., 37).

Of course, it is not easy to remain aloof from doctrinal controversy! First of all, the Army’s doctrines are clearly Wesleyan, and therefore anti-Calvinist:

In these brief 11 articles of faith, one can see the seminal Wesleyan themes of total depravity (Article 5), universal atonement (Article 6), justification by faith (Article 8), assurance through the witness of the Spirit (Article 8), and a strong emphasis on sanctification (Articles 9 and 10) (Ibid., 37).

Secondly, from the perspective of “implicit doctrine,” the obvious point of controversy would be the sacraments. Even here, a large part of Booth’s motivation was to avoid controversy.

The Army’s non-observant stance on the sacraments had its historical precedent in the tradition of the Society of Friends, but was also justified in part by the above-mentioned desire to avoid theological controversy (since the sacraments have often been a matter of theological dispute in Christian history). It was not Booth’s intent to disrespect the practice of other traditions, nor to make it a matter of dispute. Moreover, Salvationists have never been prohibited from from partaking of the Lord’s Supper in other traditions where they are welcome, and are free to be baptized if they feel it to be of importance (Ibid., 37-38).

Avoiding controversy is a noble aim, but very difficult to achieve in practice. I would suggest that recent sacramental statements of the Army have lost this early irenic tone and approach, and have become much more controversial than Booth would have liked. Also, I think one needs to be careful that a desire to be non-controversial does not become a justification for avoiding deep theological discussion, and meaningful engagement with ecumenical partners.

On March 13, Tyndale Seminary will be hosting its Fourth Annual Wesley Studies Symposium, organized by Dr. Howard Snyder, Chair of Wesley Studies at Tyndale.

On March 13, Tyndale Seminary will be hosting its Fourth Annual Wesley Studies Symposium, organized by Dr. Howard Snyder, Chair of Wesley Studies at Tyndale.